Steaks ’n’ Handshakes

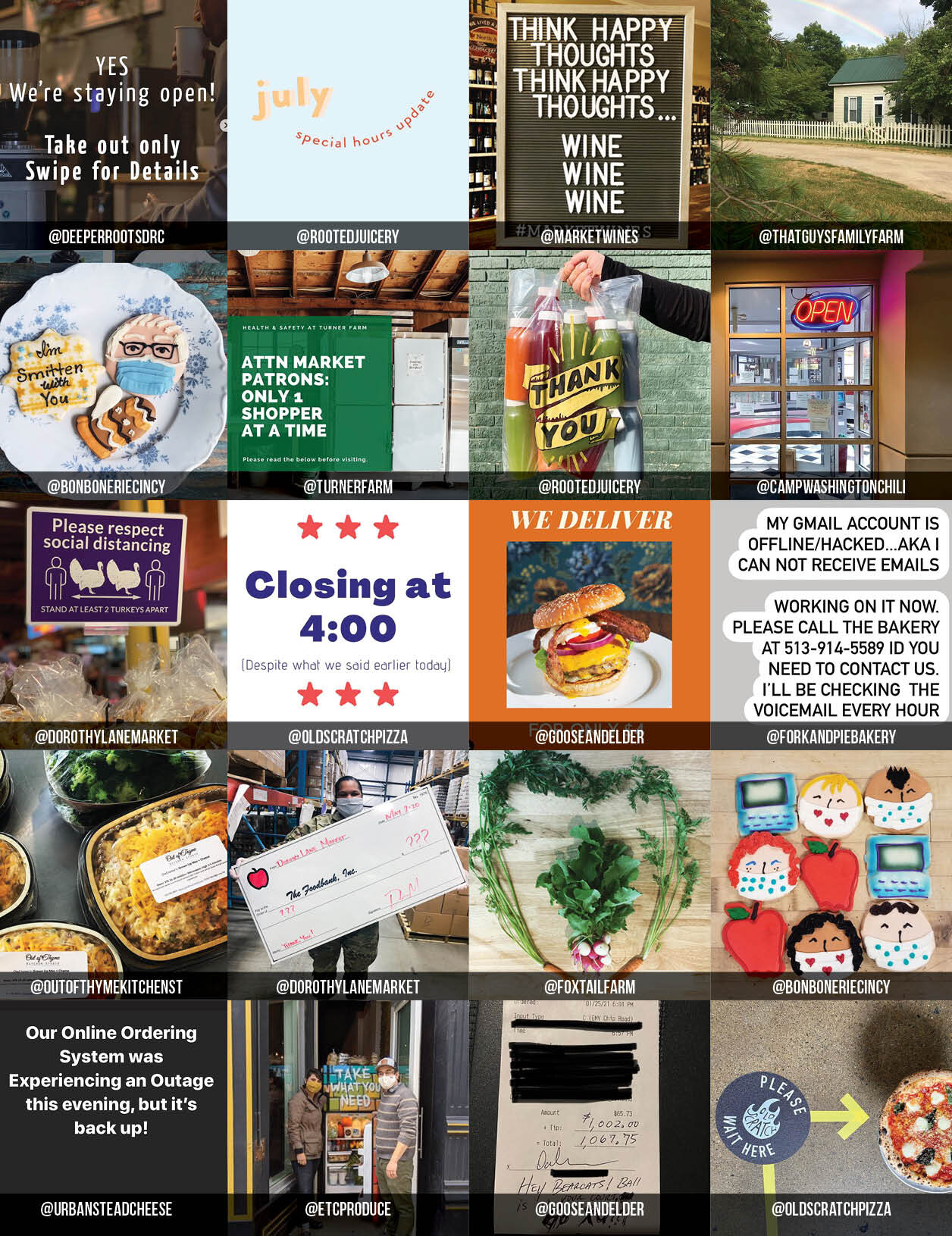

In an era of online grocery ordering and big-box retail, local independent butcher shops still have a role to play in our food community.

When I moved to Cincinnati in 1990, I was struck by the number of small neighborhood butcher shops operating in the city. There were four within a two-mile radius of our O’Bryonville apartment: Sunshine Fine Foods on Erie Avenue, Bracke’s Meats on Mt. Lookout Square, Mairose Brothers and Panzeca’s in Hyde Park. How could these small places compete in Kroger’s backyard?

And then, the shops I knew began to disappear.

Ed Bracke was ready to retire, so he sold the business to Paula Kirk; the store traded hands a few times before a fire in 2010 closed it for good. Mairose closed; in 2007 the building was razed and the property turned into a parking lot. Sunshine is now 3501 Seoul, a Korean bistro. Panzeca’s Hyde Park Meats was set to close shortly after owner Joe Panzeca passed away in 2013.

A Rare Breed

From Westwood to Eastgate, independent butcher shops have become something of a rare breed. Neighborhood shops across the area have shuttered in recent decades: Clifton Meat Market, Marty’s Prime in Montgomery, Bill and Ralph’s Choice in North College Hill, Landen Quality Meats in Deerfield Township.

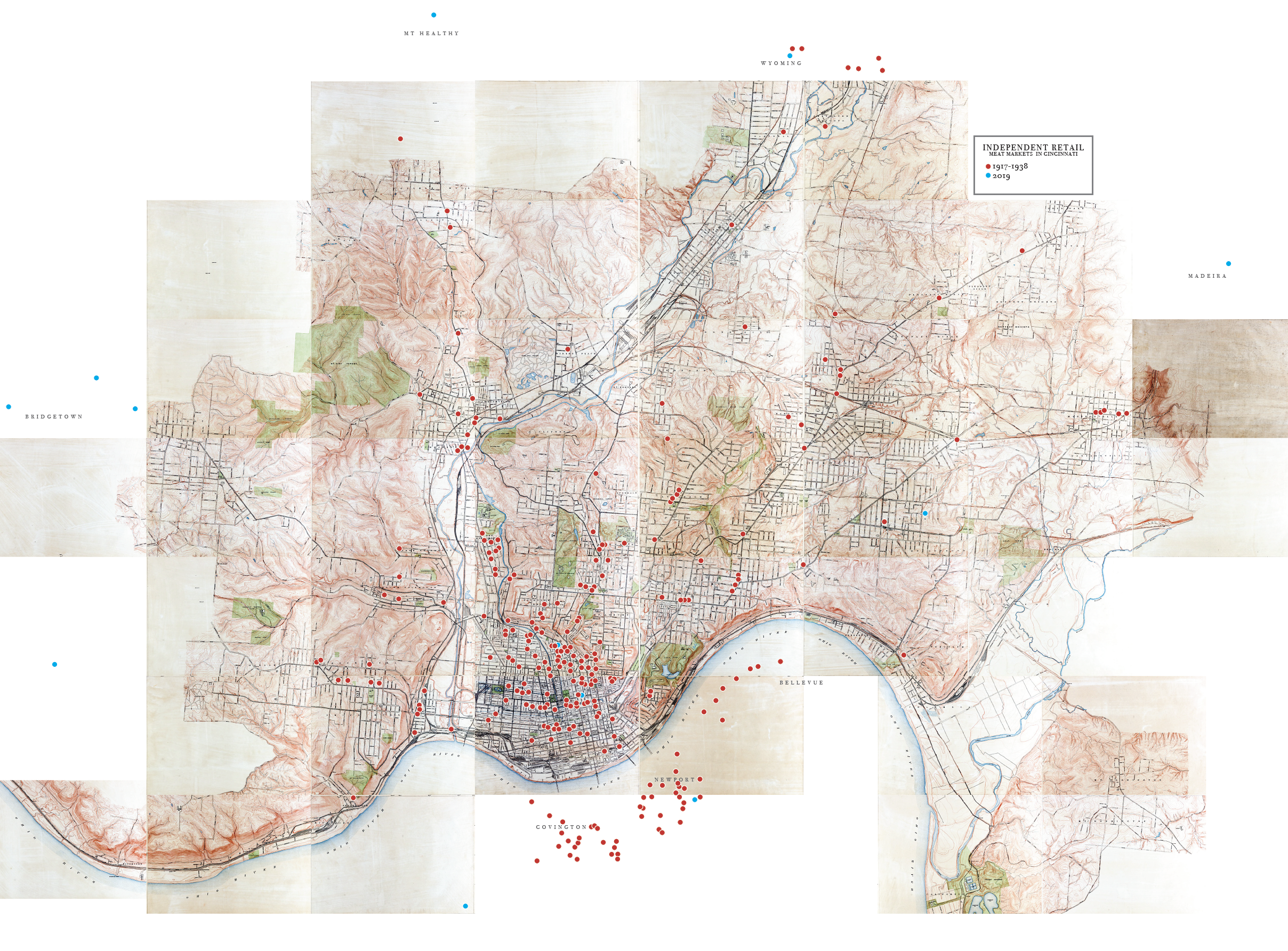

A group of advocates is researching Cincinnati’s rich food and farming history; their research hints at the former prevalence of independent meat cutters and markets in the city. Project researcher Alyssa Ryan compiled a list of retailers and processors in the city between 1917 and 1938; it includes approximately 400 local meat businesses, many of them with German names on the door: Geoppinger, Bogenschutz, Pfalzgraf, Weitzel, Lohmueller. Over time, these shops closed and faded from memory.

According to Michael Ruhlman’s excellent history, Grocery, the business of food retailing has changed dramatically since our grandparents’ day, when small neighborhood butchers, bakeries, and groceries were common. Food retailing has gone from small (independent general stores) to big (regional supermarket chains) to massive (global behemoths). In 2016, Walmart’s revenue from groceries alone outpaced the total revenue for companies like General Motors and AT&T. Our hometown Kroger has some 2,600 stores nationwide and $110 billion in sales in 2017. The world’s largest online retailer, Amazon, owns the world’s leading natural and organic foods supermarket, Whole Foods.

At the same time, our choices as food consumers have skyrocketed. Grocery stores today carry more than 40,000 different items, on average. Butter and eggs, toothpaste and shampoo, school supplies and athletic shoes—we can get almost anything we want at a big-box “grocery,” including ingredients for tonight’s dinner. What’s more, we can make our selections online, “click,” and have groceries delivered to our doorstep. All without interacting with another human being.

The business of selling meat has shifted, too, according to customer whim and business reality. In a 1984 edition of the Cincinnati Enquirer, Sara Pearce wrote of area supermarkets expanding their “service meat” departments in some stores—so called because customers could request a steak to be trimmed to order or a chicken to be cut up. But that trend has waned. Big chains chasing every last bit of efficiency to save cost in a low-margin business have shifted butchering operations to central production facilities that cut, package, and label poultry, beef, and pork for sale on store shelves.

On the Way Out

In 2013, Panzeca’s Hyde Park Meats was heading toward the same fate as so many family-owned shops in the Ohio Valley region. Owner Joe Panzeca had recently passed away; the store was set to close.

But it didn’t.

At the same time, John Ness was looking for his next opportunity. The Dayton native and his wife had spent about 10 years in what sounds like an exciting career pattern: They’d spend summer and fall working on Mackinac Island, he as an executive chef and she in hotel hospitality, then shifted to Eastern Europe for the winter and spring tourist seasons. “It was a pretty great lifestyle … until our kids came along,” Ness says. “We wanted more stability. We had just moved back from Europe and settled in Cincinnati to raise our family.”

That day in 2013, Ness recalls, “Mr. Panzeca had passed away and his widow was planning to close. I walked in on the last day they were open, and when I asked why everything was 50% off, they said they were closing.

“I went home to my wife and we talked about the opportunity,” he continues. “I was looking for something not in the restaurant world; you miss out on so much when you’re working nights because that’s when your kids want you the most.”

Ness bought the business and put his culinary skills to work, not only cutting steak, but also refining the prepared foods the shop was known for.

Lehr’s Prime Market in Milford is another local butcher shop with a turnaround story. Lehr’s has roots in a corner grocery established by the Ackermann family in 1911; partners Andy Lehr and Don Ackermann opened Lehr’s Meats in Milford in 1960. Ackermann bought Lehr’s share in the early ’80s and added a state liquor store with beer and wine in 1991.

It’s likely that booze, beer, and wine kept the store going for awhile. When Allison Homan bought Don Ackermann’s share in 2014 (Tim and Kate Ackermann remain co-owners), the meat side of the business was struggling. “Don told us to get rid of the meat department because it’ll never make money,” Homan says. “But we bought it because of the meat department.”

Homan’s own family has quite a history in the butchery and grocery business; her great-grandfather’s market in Wisconsin was known for homemade sausages and custom-cut steaks. She’d shopped at Lehr’s before buying into the business and was committed to growing the meat department. “There’s so much of the old stuff that I grew up with that we’ve brought forward,” Homan says, noting the 30-some varieties of housemade sausage. “We’ve made some decisions—like increasing the quality of the meat—that aren’t necessarily making tons of money. But it’s our passion.”

Quality Control

Quality. That’s one reason why tiny shops like Lehr’s and Hyde Park Fine Meats are still standing—thriving, even—in an age of big-box retail. Both Homan and Ness took the reins just as consumers awakened to the notion of knowing where their food comes from. For conscientious meat-eaters, the quality of the product, the treatment of the animals, and the transparency of the supply chain are important considerations.

“Our hanging sides of beef come from Buckeye Valley Cooperative out of Georgetown,” Homan says. “We carry wagyu from Sakura Wagyu Farms in Ohio. We’re working with small producers and our buying power isn’t huge, so that’s a cost issue, but it’s a whole different product, clean and healthy.”

Some markets, including Lehr’s, deal in whole-animal butchery. But most of the pork chops and ribeyes you find in local shops are sourced as primal cuts (large sections including the round, loin, or rib, which are then cut into roasts or steaks). Economics favors the latter: A half a cow contains about 4 filet mignons, for example. A shop might sell 100 filets in the few days before Christmas. Bringing in enough hanging sides to meet demand for specialty steaks leaves the butcher with an excess of the less-desirable cuts like roast or stew meat (not to mention the challenge of finding cooler space for so much beef). Lehr’s supplements with primal cuts; other shops sell them exclusively.

Running a small retail operation means proprietors can’t secure volume discounts from suppliers like the big chains can. The flip side, says Ron Holzman of Holzman Meats in Montgomery, is that he’s personally in charge of quality control. Holzman took over the business from his father and has worked the counter for nearly 50 years. He’s built solid relationships with suppliers, some of whom have delivered to the shop since day one. “There’s a Kroger store on every corner,” he says, “and they have to take whatever is sent to them. We don’t. I’m super independent. I have a bunch of vendors, and I get to choose: If I don’t think it’s good, I don’t sell it.”

Small is Big

Relationships with vendors and customers distinguish the small corner butcher shop, even from specialty grocers. “If you’re concerned about what you’re putting in your body and you want a relationship with your butcher, you don’t have that at Kroger or even Whole Foods or Fresh Market,” Homan says. “Our butchers know our customers, they know how they like their cuts. It’s a back-and-forth interpersonal relationship, and that’s key.”

Both Ness and Homan refer to the 1980s TV show “Cheers” as a point of reference for the atmosphere in their stores—a neighborhood place where customers, owners, counter staff, and check-out clerks all know one another by name.

“We know where our products are coming from and we know the quality is consistent,” Ness says. “And our faces are consistent, too. We get to know our customers by name and they get to know ours. They know they can come here and get answers. The need for a store like this is not just the quality and the friendliness, but also a guarantee that if there’s an issue, the customers can come and talk to me.”

Modest scale also allows for direct source/supplier relationships that enable stores like this to both stock locally made products and service other local businesses. Holzman, for example, supplies chicken salad to Em’s Bread at Findlay Market, and in turn buys bread from owner Melissa Engelhart. Lehr’s sells meat and sausages to 20 Brix, Little Miami Brewery, Turf Club, among others. Ness stocks locally made spice blends, Graeters ice cream, Firecracker Bakery cookies, and other items from area producers.

That said, the comparably tiny footprint of your neighborhood butcher shop makes for a tightly edited inventory of products compared to the 40,000-some items you’ll find, on average, in a grocery store. “We’ll never have room for toothpaste and shampoo,” Homan says. “But the things that really impact your life and your health, they’re all here.”

Holzman says his customers typically pick up what they need for dinner before heading up the street to Kroger for the rest of their shopping. “My dad worked in the meat business, managing meat plants for Kroger all over the country, before he opened his own business. He always said, ‘build a butcher shop right next to a grocery store, because they sell poor quality meat. Customers won’t mind making that extra stop to buy from you.’”

In the low-margin grocery business, value-added prepared items are the money-makers; that’s why small shops carve out production and display space for housemade foods like chicken salad, twice-baked potatoes, deli sandwiches, and heat-and-serve meals. “All the butcher shops make the best stuff they can,” says Ness, noting that he sells 100 pounds of lasagna and 100 twice-baked potatoes a week. “It’s all made in-house. It helps us utilize extra product and give quality products to customers who don’t have time to cook for themselves.”

Catering to Younger Customers

Surprisingly, these proprietors are seeing shifts in their customer bases. “When we purchased the business, it was definitely an older clientele,” Homan says. “The business was struggling at the time, but with the changes we’ve made our demographic has totally switched. It used to be largely from Milford; now we draw from Indian Hill, Terrace Park, Mariemont, and Loveland. The median age is probably 40 to 60, much younger than it used to be.”

Shoppers of a certain age were long accustomed to shopping trips with multiple stops: bread from the bakery, meats from a butcher, produce from a farm stand. Homan says shops like Lehr’s have to take deliberate steps to connect with younger customers. “We’ve tried to make the product more relevant. We have 30 different specialty sausages. We have a 20-tap growler bar and a walk-in beer cave. We’ve added produce. We make dog food. But we still have people coming in asking for city chicken, and we can do that for them. We’re a one-stop shop now; you can come in and get an entire dinner.”

Research conducted by Whole Foods and published this fall in Supermarket News shows that young customers are interested in healthy eating and are willing to pay more for higher-quality food. Too, they want to know where their food comes from and how it’s produced. Small markets, not just Whole Foods, are riding this trend. “It’s been important to us,” Homan says. “We were just ahead of that wave. We’re fortunate that this is where we wanted to take the business and everyone was going that way, too.

“It’s not like you’re buying a scarf, it’s not something ancillary,” she continues. “You’re feeding your family. It’s part of your life and livelihood and you want to trust who you’re dealing with. This is not a new concept. We’re coming back to what makes sense. It’s well-honed. It’s not a trend. It’s going to stay.”

One wonders if more of the old butcher shops that could be found in neighborhoods across the Ohio Valley might still be here if they could have managed to hold on a few years until the healthy eating and locavore movements took off. It’s a small sample size, but for the three owners we spoke with, business is thriving. “In the very beginning, business stuff would keep me up at night,” Ness says. “But we’ve been able to grow the business so well that I’m not staying up at night anymore. I wouldn’t want a business that keeps me up at night. I’m doing this for the pleasure of owning my own business, but also to have a family life.”

Ever self-effacing, Holzman talks modestly about building a successful enterprise on sensible decisions and good luck. He chuckles at the question of retirement. His father never retired, not really, working until he couldn’t any more. (Holzman’s parents’ final resting place is the Gate of Heaven cemetery directly across Montgomery Road from the market; he figures they’re keeping a close eye on things.)

“I love what I do,” Holzman says. “The people are the best part of it. Business is very, very good. I have no complaints. But there’s nothing left over; it all goes right back into the business, which is pretty common for a small business.

“My dad was right: You’re not going to get rich in this business, but you’re always going to eat well.”

Bryn’s long career in publishing took a left turn sometime around 2010, when she discovered the joy of food writing. Since then, she’s found professional nirvana as the editor of Edible Ohio Valley, author of The Findlay Market Cookbook, and occasional instructor at The Cooking School at Jungle Jim’s. Find her seasonal recipes at writes4food.com.