The Butterfly Effect

Gardeners across the Ohio Valley can take simple steps, right in our own backyards, to counteract the effects of global climate change.

In the 1960s, MIT meteorologist and mathematician Edward Lorenz developed a theory popularly known as “The Butterfly Effect.” He observed that tiny changes in early conditions can lead to wildly different outcomes in large, fluid systems down the road.

The idea was somewhat misrepresented in the public’s imagination as a butterfly wing flapping in Brazil altering the course of a tornado in Texas. What Lorenz actually meant to underscore was the unpredictability of vast systems like the environment.

Simple practices in the garden will, in the vast, fluid system of the globe, influence events on a global scale.

It’s an apt metaphor for the plight of individuals, particularly gardeners, whose work might address one of the biggest problems of all. In gardening lies the hope for an increasingly grim future. And the steps gardeners can take for the long-term, larger good offer immediate benefits for their resilience in uncertain climes.

A TELLTALE SIGN

For Ohio State University Extension Educator Joe Boggs, as for so many Ohio Valley gardeners, the canary in the coal mine of climate change, as it were, came with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s revision of their Zone Hardiness Map.

“What that’s telling us is that warmer temperatures are rolling north, and that’s been going on for some time,” he says. But he cautions: “The USDA zone map is based on averages. You’ve got to be careful about averages.”

The USDA Zone Hardiness map divides regions into 10-degree zones based on average annual minimum winter temperatures. The shift in zones, which began in the 1990s and resulted in a 2012 update to the Zone Hardiness Map, puts all of Ohio, previously split between Zone 5 (-20°F to -10°F) and 6 (-10°F to 0°F) entirely in Zone 6.

Some climate models suggest that by 2040, Ohio could be Zone 7 (0°F to 10°F). While Boggs cautions against jumping to conclusions about what climate change will mean for any specific locale, it is already changing ecosystems, affecting the ranges and timing of plants, pollinators, and pests. For example, Boggs says, bagworms, previously unseen north of Interstate 70, are now surviving winters as far north as southern Michigan. The warming of just a few degrees could push the Ohio Buckeye north, extirpating it from the Buckeye State.

What does all this mean on a pragmatic level for growers here, on the cusp between north and south? Of one thing Ohio Valley gardeners can be certain: uncertainty to come. Uncertainty in weather patterns and ecosystems, in what tried-and-true practices will and won’t work for a better future. We might be looking at a longer growing season, Boggs says, but increased volatility might also bring occasional polar vortexes, deluges, drought, and new threats from diseases and pests.

WHAT GARDENERS CAN DO

Growers in the Ohio Valley have been dealing with climate change for millennia. Pollen from bog sediment samples taken near Athens, OH, shows dramatic climactic shifts driving ecological and agricultural change as a great warming and drying period brought grasslands and the return of forests. Samples even show evidence of large-scale burning by prehistoric and early-historic peoples for agricultural and forest management. While climate change has been constant, and with it changes in ecosystems, the human-caused warming of the planet from greenhouse gasses, left unchecked, will bring catastrophic change.

WE CREATED THIS. WE CAN FIX IT.

The biggest tool in our climate arsenal is agriculture. Scientists believe that carbon-friendly agricultural and land-management practices could, if widely implemented, balance global carbon emissions. In conjunction with lower emissions, we could dramatically slow global warming.

According to Eric Toensmeier, author of Carbon Farming: A Global Toolkit for Stabilizing the Climate with Tree Crops and Regenerative Agriculture Practices, and based on Rodale Institute data, a tenth-acre backyard garden could offset the carbon emissions of one American adult per year. Growing your own food is itself carbon friendly, as the average piece of store-bought produce travels 1,500 miles, requiring the expenditure of fossil fuels. But making your garden more effective at removing atmospheric carbon directly counteracts climate change’s cause.

That’s because plants drive the carbon cycle.

During photosynthesis, they draw carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and convert it into carbon-based sugars. Some of these get released into the soil, where fungi and microbes convert them into nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients. This process develops a microbial and fungal culture in the soil from which plants get most of their nutrients.

Mycorrhizal fungi generate a gummy protein called glomalin that is about one-third carbon and very long-lasting. Thus, humus is born. Humus is both permeable and porous, absorbing water during those heavy rain events we can expect to see more of, and storing it through dry periods, also on the upswing. Humus is also about half carbon. Regenerative gardening practices build that top, humus-rich soil layer. The deeper and richer your soil is, the more carbon it retains—potentially for hundreds, even thousands of years.

COMPOST!

Composting is the No. 1 thing home gardeners can do to increase your landscape’s carbon capture, says Great Parks Glenwood Gardens Naturalist Doug Stevenson. Climate change has been very much on garden managers’ minds at Glenwood, he says, because they track bloom and pollinator arrival times.

“Take your leaves and lawn clippings and garden waste and turn that into mulch or compost,” Stevenson advises. “Not only does that keep it out of the landfill, but it reduces methane emissions, helps improve the garden soil, and helps to store carbon.”

Glenwood has also experimented with biochar, he says, with spectacular results. Biochar is just what it sounds like: charred organic matter that, used as a soil amendment, boosts soil’s carbon sequestration and fertility. At Glenwood Gardens, the team has seen healthier plants and brighter blooms. It’s being studied as a possible alternative to peat, which you should avoid because peat bogs are excellent carbon sinks—until they’re dug up to satisfy our appetite for nice, fluffy potting mixes.

While you’re increasing the carbon in the ground, it’s important to keep it there by limiting how much you disturb the soil. Low-till techniques and good soil cover are key, says Cincinnati State Sustainable Agriculture Professor Heather Augustine, who also manages over 100 community crop plots at St. Clare convent in Hartwell.

To keep soils intact and healthy, she recommends tilling only when absolutely necessary. “Our soils are notorious for being heavy and challenging,” she says. “So what do we do? We till with reckless abandon.” That breaks down soil integrity and allows oxygen to mix with stored carbon, creating carbon dioxide gas. “In other instances, we leave perfectly good soil completely bare. So when increasingly strong or lengthy rain events occur, the topsoil, where nutrients and microbial life reside, washes away.” Planting a cover crop over fallow beds increases carbon retention, prevents erosion, and improves soil.

DIVERSIFY!

What we plant in that rich, carbon-absorbing soil is equally important to a garden’s climate-change resilience and resistance. Ecosystems’ ability to survive and adapt derives from their biodiversity, offering wildlife a spectrum of food- and host-plants, supporting a network of beneficial relationships, and maintaining capacity to respond to new conditions, population dips, and explosions. (I’m looking at you, aphids.)

“Focus on biodiversity in selections at the garden center and try to plant as many perennials as possible since they tend to be more resistant and easier to maintain,” Augustine says. “Look for plants that have a broad hardiness range.” This will ensure the plant’s success through temperature changes down the road, she says. Include species that can tolerate both very wet and dry periods. “Plants that are native to our area are well suited to the extreme weather fluctuations we have been experiencing.”

Co-planting a vegetable garden with hardy natives, which have deeper root structures, deepens the carbon-, water-, and nutrient-retaining soil layer, and provides water management co-benefits to your more tender veggies.

It’s also important to consider wildlife. At Glenwood Gardens, Stevenson plants an array of milkweeds for the monarch butterflies, so that if one species has a bad season, there’s an alternative.

And think outside your garden beds. Plant trees, the most efficient means of carbon sequestration, which generate their own microclimates and, through evapotranspiration, cool their vicinity.

I met lifelong gardener and former urban farmer Kevin Fitzgerald back in 2014, when he was a partner in the Urban Greens community-supported agriculture program. That business is no more, but the Urban Greens garden where I met him spread across a derelict lot just nine feet above flood stage near the bank of the Ohio River. It was one of those gardens with a microclimate you could sense from the interplay between the plants and their relationship to the surrounding environment. A tall perimeter of sunflowers, cannas, and amaranth attracted pollinators, beautified the place, and acted as a windbreak for the tender vegetable beds.

Today, Fitzgerald helps his wife, Lauren Wulker, with her dried-flower arrangement business, Restorative Roots. At their home, Fitzgerald continues to plant a perimeter of protective, hardier plants around their vegetable garden.

Fitzgerald has been studying the movement of weather on the radar. “I’ve noticed a lot of our rain comes from the south and kind of drifts a little bit north. It keeps drying out and getting busted up by the heat island of downtown.” While nearby localities get a drink, his neighborhood doesn’t. This underscores human influence on weather, and the ways in which even a small city, especially with our hills and valleys, has climate variation neighborhood to neighborhood. You probably noticed this over the summer: You’d drive through a pounding rain, only to reach dry pavement when you get home.

Fitzgerald plans to add irrigation infrastructure to his home garden, and you should consider it, too. Rain barrels and efficient irrigation methods like soaker hoses and drip systems minimize evaporation loss and reduce both water consumption and carbon loss. And they’ll help you ride out the drought-or-dump situations we find ourselves in. Fitzgerald also likes a simple, climate-friendly hack: He upcycles garden and yard waste and spreads grass clippings among his beds to create a protective layer.

With a challenge as great and complex as climate change, Augustine says, “it may make it seem like there is little one can do to make a difference.”

But simple practices in the garden will, in the vast, fluid system of the globe, influence events on a global scale. Consider that climate change is also a cultural problem, caused by human behavior—so changes in human behavior must be part of the solution.

Here too, gardens and gardeners partake of the power of that butterfly. These small acts collectively build community support for carbon-friendly practices on a mass scale, in big agriculture, in the energy sector, and across organizations and economies.

It’s impossible to know what effect a single butterfly will have. But where it lands, there’s hope, growth, and the means to make a better, greener future.

Simple practices in the garden will, in the vast, fluid system of the globe, influence events on a global scale.

From Alfalfa to Vetch

Cover Crops for the Ohio Valley (some are edible)

Cover crops vary on when they can be planted. Some, such as legumes, fix atmospheric nitrogen into a form plants and microorganisms can use. Non-legume species recycle existing soil nitrogen and other nutrients and reduce carbon losses.

Legumes

Alfalfa

Annual Medics

Clover

Field Peas

Hairy Vetch

Oilseed

Soybean

Non-legumes

Buckwheat

Forage Turnips

Oats

Rye

Spelt

Sudangrass

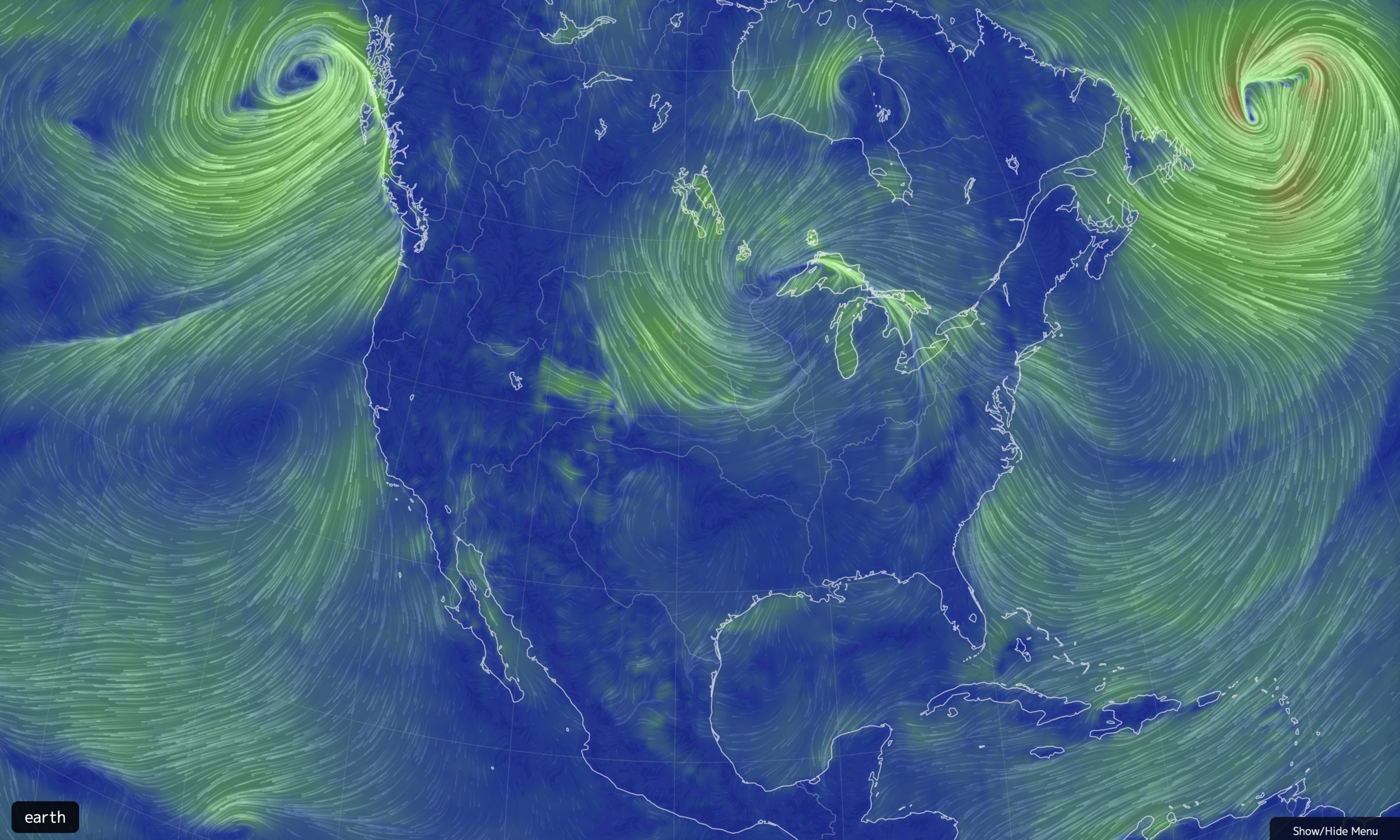

Illustration: Track global wind, waves, and currents online at earth.nullschool.net

Ever since his grandfather put him to work squashing potato bugs and shoveling compost in a vast organic garden north of Philadelphia, Cedric has loved the outdoors. These days, he squashes bugs for his green-thumbed partner, Jen. His writing has appeared in Saveur, Cincinnati, This Old House, and Belt magazines. He is the Collector at the Mercantile Library Downtown.