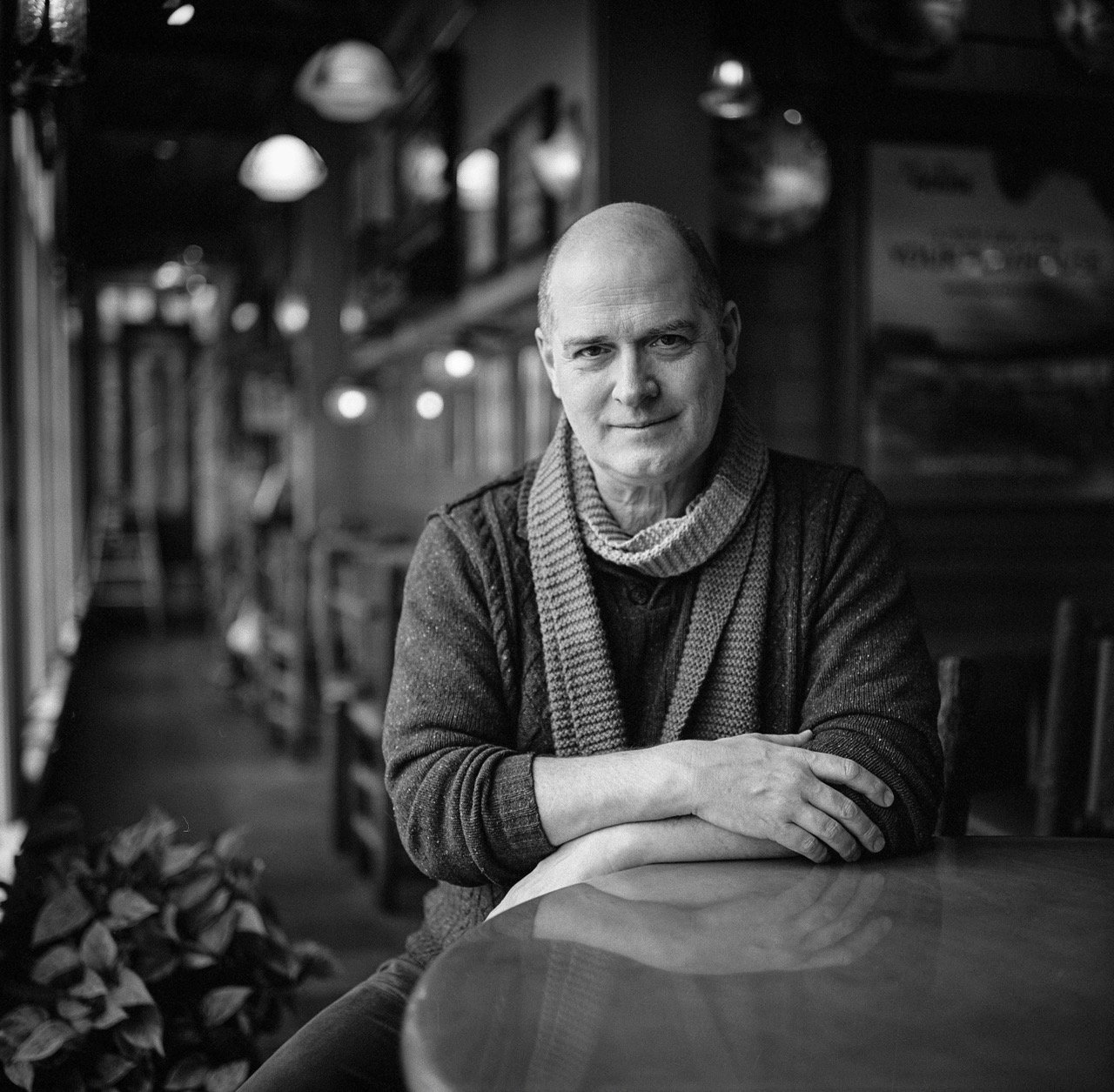

Thane Maynard

Over a lunch of local food prepared by Executive Chef Dana Atkins, the Cincinnati Zoo Director talks about eating like an animal.

Portrait by Michael Wilson

What are the issues at the intersection of food, sustainability, and wildlife conservation?

The biggest human use of land is agriculture. We’ve gone into wild areas and clear-cut or plowed and turned it into farmland. We need to do that, of course, but we need to figure out how to do it smarter with less dangerous pesticides and more efficient use of land. Those are big questions everywhere, particularly in the developing world.

Help us connect the dots between our food choices and wildlife.

The way we eat is the No. 1 thing people can do about their own personal health, their carbon footprint, and their environmental impact. A good example is palm oil. It’s historically been used in a lot of things, and it had a huge surge a few years ago when trans fats were recognized as bad. The problem is that everyone with a chainsaw clears forest in the tropics and grows palm oil. That destroys habitat for all kids of species, notably orangutans, forest elephants, and rhinos. Look at the label: Does your food product have palm oil? Make choices for alternatives. You can do it, and then it becomes a habit.

Even zoo animals get local food; talk about the Zoo’s farm.

It’s in Warren County near Mason. It’s not a farm full of zoo animals, but we take our cheetahs up there to run once a week. We grow a lot of food for our animals — hay, river oak, mulberry, bamboo — and native plants for the Botanical Garden.

What can we learn about eating from our fellow mammals?

It’s not conjecture to say that animals eat better than people. We’re like raccoons: We can eat anything, but long term that’s not going to be beneficial to our health. Many many species are very specialized, mostly herbivores. We’re relatively large animals; we’re warm-blooded and active and so we’re hungry all the time. Many mammals eat very seldom and have much lower metabolisms than we do.

I’m really proud of our Eat Like an Animal program, which celebrates what animals eat and why.

We’ll compare two animals that look alike but eat totally differently, like a manatee and a walrus. Walruses are hunters, they’re built for that, they carry a lot of fat and can live in really cold climates. Manatees are only plant-eaters; they eat sea grass and water hyacinths. And as a result they have a completely different metabolism and can only live in warm water.

Hopefully people come away with a sense of wonder. We’re here to plant seeds and help people think about how they get along in the world.

So what animal should we model?

I’d say black bears — a small percentage of their diet is meat and the vast majority is plants, which is what modern nutritionists suggest.

How does the Zoo educate folks about issues like sustainability or health?

I love our kale salad, but we’re not going to tell people you can only eat kale salad when you come here. The Zoo tries to model good behavior, not to be preachy. We’re here to inspire people with animals. Nobody wants to come to the Zoo to be lectured at about climate change and our responsibility for it; they want to be inspired by these animals so they’ll take their own steps to make sure they’re still around in 100 years.

Why are we so enchanted by videos of Rico the Brazilian porcupine eating peanut butter or Fiona eating watermelon?

Because people enjoy eating, we love seeing animals eating, too. It’s anthropomorphism: You see Rico eating peanut butter off a spoon and think, “Hey, I do that, too!”

What’s always in your fridge?

Apples! I eat a couple of apples every day.