Talking Turkey

Planning a glorious roasted turkey for your family’s holiday table? Here’s the scoop on where—and why—to buy a local bird.

It’s something we prepare just once or twice a year, but we certainly take our holiday turkey seriously. We brine, we season, we stuff, and we roast. Cooking magazines devote their November covers to it. We scour the internet for new and different recipes. We grill, we deep-fry.

And while we might think of the Thanksgiving bird simply as a ‘turkey,’ there are actually many different varieties. The bird we bring to our tables year after year is most likely the Broad-Breasted White, which has been the most popular variety since the 1950s. As its name suggests, it’s the culmination of breeding efforts begun in the 1920s to create a turkey with an abundance of white breast meat.

It’s still the bird of choice for local farmers today, thanks to its relatively quick maturity period (about five months) and the continuing high demand for white turkey meat.

While we can purchase a Broad-Breasted White turkey at any grocery store, local birds are raised quite differently than conventional. Not only does that translate to a product that we can feel good about serving, it makes for a tastier holiday centerpiece.

LETTING TURKEYS BE TURKEYS

“It’s an incredibly high percentage of turkeys that are raised in high confinement with antibiotics,” says Marc Luff, who raises turkeys on Finn Meadows Farm in Montgomery. “We try to improve on that and give the animal a dignified life where they get to do whatever they want to do. It’s not perfect, but we balance producing an affordable product in the most ethical way we can,” he says.

Instead of cooping them up in crowded quarters, Luff and other local farmers let their birds roam free. However, the chicks haven’t learned enough to be able to safely spend their days in a pasture right away. Turkeys spend their first weeks warm and safely tucked into a barn or greenhouse. Then farmers transition young turkeys, or poults, out into small, portable pens in the pasture that get moved around every few days to give them access to fresh grass.

This way they have protection from predators and the elements as they grow into adulthood. “If they’re out in the pasture too soon, they’ll look up at the rain and swallow it and drown,” explains Luff. (Turkeys aren’t known for their smarts.)

Interestingly, the biggest predatory threat to juvenile turkeys isn’t generally foxes or hawks as you might expect, but rather owls. “I’ve lost a number to owls, especially when they’re young,” says Luff. “The owl will come up to the side of the coop, grab the head or the leg and tear it off.”

Once the birds reach a certain stage of maturity, they can have free range of the pasture, although many farmers still maintain some kind of border for safety. For example, Luff secures his acre of turkey pasture with an electrified fence. “The more space you give them, the more they’ll walk—way more than chickens. With those long legs, they can cover a lot of ground,” he says.

That movement helps the turkeys develop muscle tone, which translates into a strong, lanky bird. That defined musculature helps them withstand processing, which includes being chilled in a water bath for several hours. Conventionally raised turkeys tend to absorb a lot of water during this process, while pasture-raised birds hardly absorb any thanks to their well-developed muscle tone.

The other major difference between conventional and pasture-raised turkeys is what they’re fed. Most local farmers make their own high-quality, non-GMO meal or purchase one. It’s generally made up of whole- roasted cornmeal and soybean, fish meal, and vegetable scraps. Additionally, local farmers do not treat their turkeys with antibiotics.

Since they’re pasture-raised, a good portion of their diet consists of what they can forage for themselves, including grass and bugs. Luff estimates that his turkeys’ diet is made up of a third to a half bugs and grass at Finn Meadows. In fact, athletic turkeys can even be seen running and launching themselves in the air to catch a grasshopper in mid-flight.

HERITAGE BREEDS

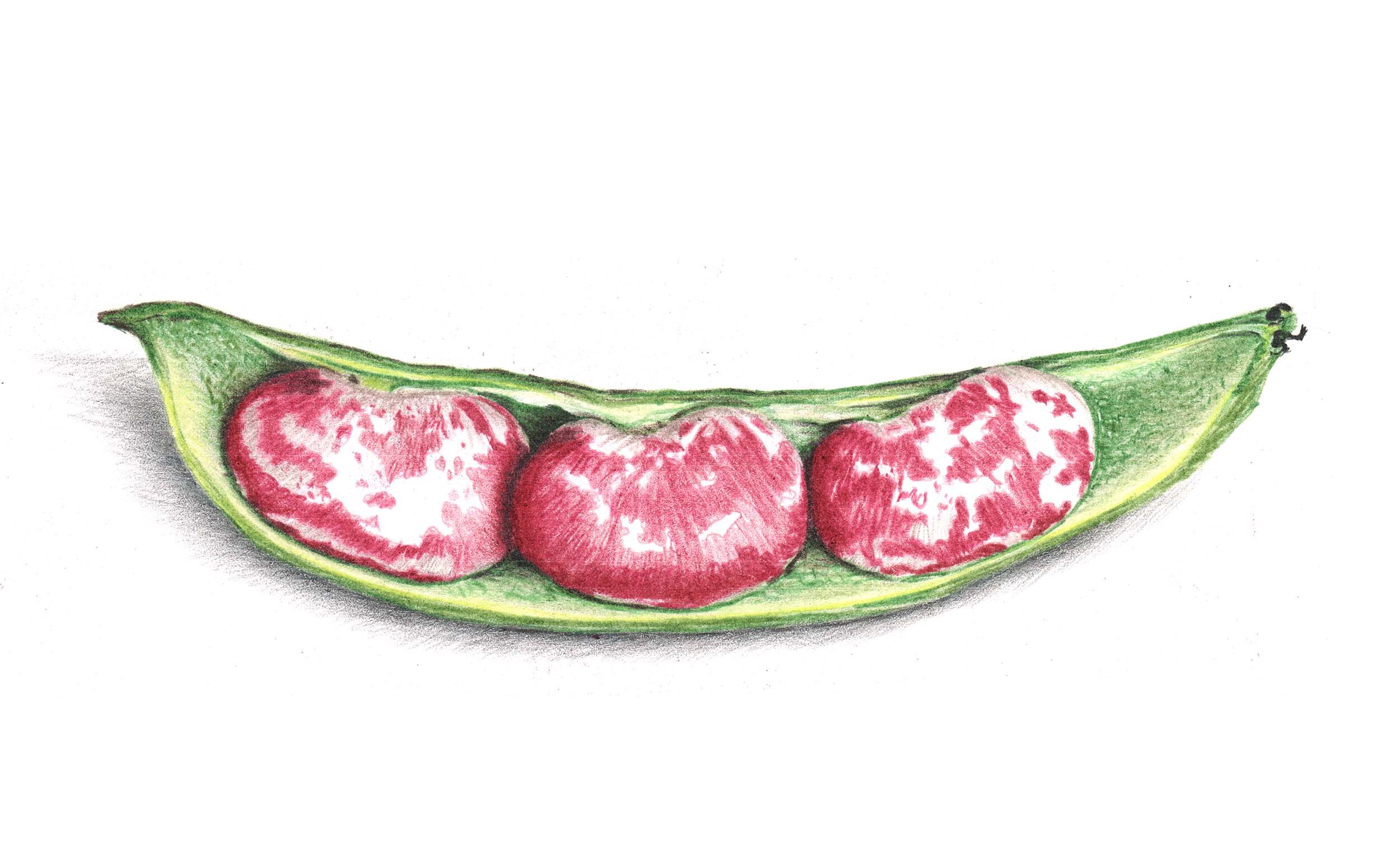

While the Broad-Breasted White turkey is a bird sold predominantly in the U.S. and raised locally, there is a slow trend toward returning to heritage breeds. These varieties, like Bourbon Red, Narragansett, White Holland, Black, Bronze, and Beltsville Small White, generally have darker and more varied plumage, which is one of the reasons they fell out of fashion. The darker pin feathers make the dressed birds look darker in color, not the pure, smooth white color of a plucked bird we’re accustomed to today. They also have more dark meat, a gamier flavor, and take longer to mature.

The American Poultry Association lists a few standards that a breed must meet to be considered heritage, including the ability to mate naturally and a slow growth rate (around 28 weeks, 8 weeks longer than the Broad-Breasted White). Surprisingly, the Broad-Breasted White doesn’t meet that first requirement, as it’s unable to reproduce in the wild. The birds require artificial insemination to produce fertilized eggs, and farmers must order chicks rather than breeding their own turkeys.

As we collectively turned toward the Broad-Breasted White, many heritage turkey breeds were nearing extinction just 20 years ago. A count in 1997 showed only 1,335 heritage turkeys in the entire U.S.

In response to the dwindling numbers, there has been a recent push to encourage farmers and hobbyists to once again raise heritage breeds. However, they are more expensive to raise since their maturation period is longer, and many farmers say that the demand for darker-meat birds simply isn’t there. “It is true that there needs to be consumer demand in order to sustain the breeds,” says Ann Stone, who, with her husband, Mac Stone, raises Narragansett and Bourbon Reds at their Elmwood Stock Farm in Georgetown, KY. (Morning Sun Farm in West Alexandria, OH, is the only other local farm to produce heritage turkeys.) “We count on the increased interest in serving a heritage turkey at Thanksgiving, Christmas, or other special events as a way to help cover the high costs of raising the turkeys each year and keeping the breeding turkeys.”

Heritage breeds, Stone says, have a different taste that some customers prefer. “The meat is full of flavor; I would describe it as rich and complex. Almost like comparing lobster to fish. The turkeys are more mature at harvest, so there is more natural fat, which keeps the meat from being dry.”

CULTIVATING BETTER FLAVOR

Of course, the real question is: Does all this care in raising and feeding change the taste? “A lot of our customers say it’s the best turkey they ever had,” says Luff. “I think a lot of the reason is exercise. The meat is juicier, and the bugs and grass change the Omega-3 and Omega-6 makeup. It has a little more of a wild flavor to it, which most people like.”

Patty Schwartz, of Back Acres Farm, has had similar feedback from her customers. “People will tell you that the flavor and texture is beyond what you could imagine. It’s just a very healthy bird. The turkey that you get in the store, with the pop-up timers and injected with a solution—I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with them, but if you want a pure, healthy turkey that hasn’t had anything done to it, you’ll be happy with one of our turkeys,” she says.

With so many choices available close to home, it’s certainly easy to bring home a local pasture-raised turkey for this year’s Thanksgiving dinner—and to taste the difference for yourself.

FRESH, NOT FROZEN

One of the major differences between buying a locally raised turkey and purchasing one from most grocery stores is that local birds come to you fresh, never frozen. They’re processed just days before Thanksgiving and kept chilled until you can pick up your bird, many times the day before Thanksgiving or even on the day itself, in some cases. That means you can simply brine or rub your turkey and put it directly into the oven—no long thawing times required.

ORDERING BASICS

Since local turkeys are processed so close to Thanksgiving Day, farmers can’t say for sure which sizes of bird they’ll have available. Most of them ask that you simply order the approximate sized turkey that you’ll need ahead of time, and they’ll match your order as closely as possible to what they have available after processing. As a general rule, you’ll want to order 1 1 ⁄ 2 pounds per person for larger birds (15–20 pounds) and 2 pounds per person for smaller birds (12 pounds or less) because they have a smaller meat-to-bone ratio. Pro tip: Tewes Poultry recommends you bring your roasting pan when you pick up your turkey to make sure the bird fits.

Where to Buy A Local Turkey

AVRIL-BLEH, Downtown Cincinnati.

A full-service butcher shop. Ask for local turkeys this year and they are willing to sell ½ turkeys if you ask! Pick up at the store or ask for Saturday delivery.

Call to order: 513.241.2433

DOROTHY LANE MARKETS

Find local turkeys from Bowman and Landes Farm at all 3 Dorothy Lane Markets

EATON FARM (Certified Organic) Madison, IN

812.839.6452 TheEatonFarm.com

Place order online using request form.

ELMWOOD STOCK FARM (Certified Organic) Goergetown, KY

859.621.0755

Place order online using request form. Pick up at Hyde Park Farmers Market or Hyde Park “Turkey Tuesday” Celebration. Home delivery and shipping options also available.

GREENACRES Cincinnati, OH

513.891.4227

Place order in advance, on farm pick-up

HYDE PARK FINE MEATS

A full-service butcher shop. Ask for local turkeys.

Call to order: 513.321-4328

KOPP TURKEY FARM, Harrison, OH

Purchase at Whole Foods, and at Luken’s at Findlay Market.

LEHR’S PRIME, Milford

A full-service butcher shop. Ask for local turkeys.

Call to order: 513.831.3411

TEWES POULTRY, Erlanger, KY

Place order in advance, on farm pick-up

Call: 859.341.8844

TS FARMS (non-GMO) New Vienna, OH

937.763.1167 tsfarmsoh.com

Place order & deposit in advance online.